Printemps des Peuples: The Springtime of Peoples (1848)

While the Bourbon Monarchy is mainly known in modern America for its decadence and aid to America during the War of Independence, it is less commonly recognized that the dynasty was restored. After the War of the Eight Coalition, during which Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo, a period known as The Restoration began. Although the Bourbon monarchy regained control, the Ancien Régime and its Estates never returned. France, reshaped by the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, had uprooted the power of the First and Second Estates while empowering the middle and upper classes that supported the revolution. In the 1790s, the Catholic Church lost much of its land and influence as Paris sought to stabilize public finances and responded to revolutionary distrust of the Church’s power. Furthermore, Napoleon solidified state dominance over the Papacy by crowning himself instead of allowing the Pope to do so.

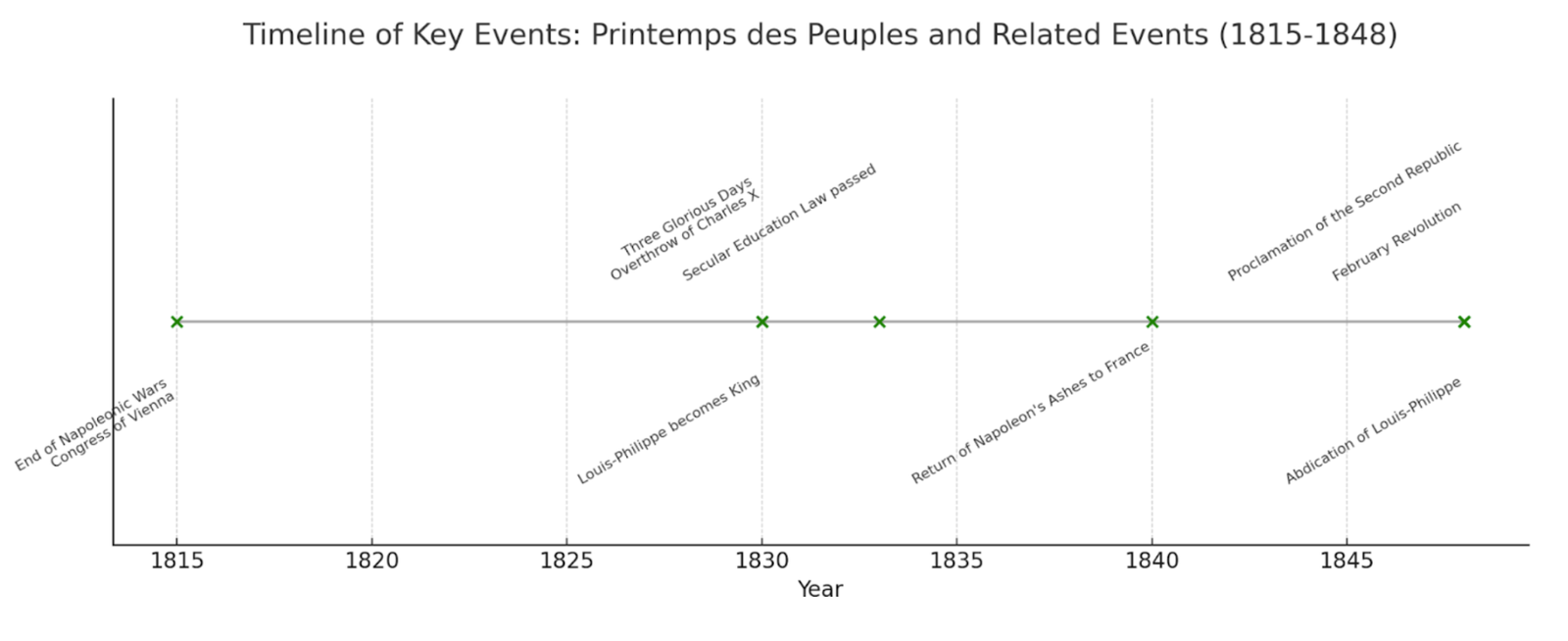

In 1830, widespread unrest led to three days of riots, known as the Three Glorious Days, from July 27th to 29th. This uprising resulted in the overthrow of Charles X. Following his cousin’s downfall, Louis-Philippe returned from exile and consolidated power, becoming King of the French on August 9th. This title marked a significant shift from prior monarchs, who were styled as Kings of France, emphasizing his role as a king for the people rather than a despot. Upon ascending the throne, Louis-Philippe sought to provide stability after decades of turmoil, presenting himself as a “Citizen King” who aimed to balance the demands of radical republicans and legitimists—those who supported the old Bourbon monarchy. He drew inspiration from the more liberal British parliamentary system.

Louis-Philippe’s early life was shaped by his father, Philippe Égalité, a progressive nobleman and supporter of revolutionary ideals. As the eldest son, Louis-Philippe received an education grounded in Enlightenment principles. However, the execution of his father by revolutionaries forced him into exile, during which he lived in various European countries and the United States. These experiences profoundly influenced his views on governance, as he witnessed both the tyranny of absolute monarchy and the chaos of unchecked popular power. His rule reflected a desire to avoid these extremes, aiming instead for moderation.

As king, Louis-Philippe sought to modernize the monarchy, making it more representative of contemporary and Enlightenment ideals. He introduced reforms such as adopting the red, white, and blue tricolor flag, symbolizing unity and revolution. He also championed freedom of the press and, in 1833, supported Education Minister François Guizot’s passage of a law establishing secular education as a right. Guizot, later serving as Foreign Minister, worked to improve relations with Britain. Louis-Philippe also honored France’s cultural heritage by transforming the long-abandoned Palace of Versailles into a museum celebrating French history. These actions set him apart from reactionary predecessors like Charles X, who adhered to the outdated ideals of the Ancien Régime rather than embracing the constitutional monarchy established by the Charter of 1814.

Despite his initial popularity, Louis-Philippe’s reign became increasingly strained by 1848. Economic challenges and his refusal to further liberalize the political system alienated many French citizens. In February 1848, tensions boiled over when Guizot banned a republican banquet advocating universal suffrage. His opposition to electoral reform, which maintained a steep property qualification for voting, angered liberals, republicans, and socialists alike. The ban on the banquet sparked unrest in Paris, leading to widespread protests and violence. Unable to restore order, Louis-Philippe abdicated on February 24th, 1848, paving the way for the proclamation of the Second French Republic. However, the republic was short-lived as a new Napoleon rose to power, amended the constitution, and declared the Second French Empire within five years—justifying it through a referendum that secured 66% of the vote.

The effects of the “Springtime of Peoples” were not limited to France. In 1848, efforts in Frankfurt to unify the German Confederation and offer the crown to the Prussian monarchy failed. This revolution sought to establish a constitutional German state that was more liberal than what many of the diverse states desired, contributing to its failure.

As a result of the Springtime of Peoples, the Austrian Empire had to fight to maintain its domain over Hungary, with the aid of the Russian Empire, after defeating a republican revolution in Vienna. In Italy, an Italian Legion attempted to unify their divided nation. While most of these revolutions ultimately failed to achieve their goals, some of their aspirations were realized in the long term. The North German Confederation and Italy unified in 1871, and the Austrian Empire made further concessions to Hungary, forming a dual monarchy years after the Hungarian War for Independence. Germany's unification also led to the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine after defeating France, fueling resentment that contributed to the First World War. Following the Franco-Prussian War, Napoleon III’s monarchy fell, and the Third French Republic was declared, ending the empire established through his earlier referendum. Consequently, the Second French Empire collapsed, paving the way for a more republican France, fulfilling many aspirations of the 1848 revolutionaries.

Citations

Bouchon, Lionel A, and Didier Grau. “Domestic Politics.” Napoleon & Empire, 11 July 2015, www.napoleon-empire.org/en/first-empire-domestic-politics.php.Delage, Irène, and Nebiha Guiga. “Napoleon III, Emperor of the French (1808-1873) - Napoleon.org.” Napoleon.org, Napoleon.org, 25 May 2016, www.napoleon.org/en/young-historians/napodoc/napoleon-iii-emperor-of-the-french-1808-1873/. Accessed 25 Dec. 2024.

“La Révolution de Février 1848.” RetroNews - Le Site de Presse de La BnF, 2024, www.retronews.fr/cycle/la-revolution-de-fevrier-1848.

Limbach, Eric. “March 1848: The German Revolutions | Origins.” Origins, 20 Mar. 2023, origins.osu.edu/read/march-1848-german-revolutions.

“Louis Philippe I.” Palace of Versailles, 4 Jan. 2018, en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/great-characters/louis-philippe-i.

Mutschlechner, Martin. “The Hungarian War of Independence 1848/49.” Der Erste Weltkrieg, 17 Aug. 2014, ww1.habsburger.net/en/chapters/hungarian-war-independence-184849.

“Napoleon III.” Palace of Versailles, 4 Jan. 2018, en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/great-characters/napoleon-iii.

“Risorgimento.” Ohio.edu, 2024, sites.ohio.edu/chastain/rz/risorgim.htm.

Thierry Sarmant. “LOUIS-PHILIPPE OU LA CARTE DU ‘JUSTE MILIEU.’” Historia, 11 Apr. 2022, www.historia.fr/personnages-historiques/biographies/louis-philippe-ou-la-carte-du-juste-milieu-2061768. Accessed 25 Dec. 2024.