Civil War Draft Riots: A Rich Man's War and a Poor Man's Fight?

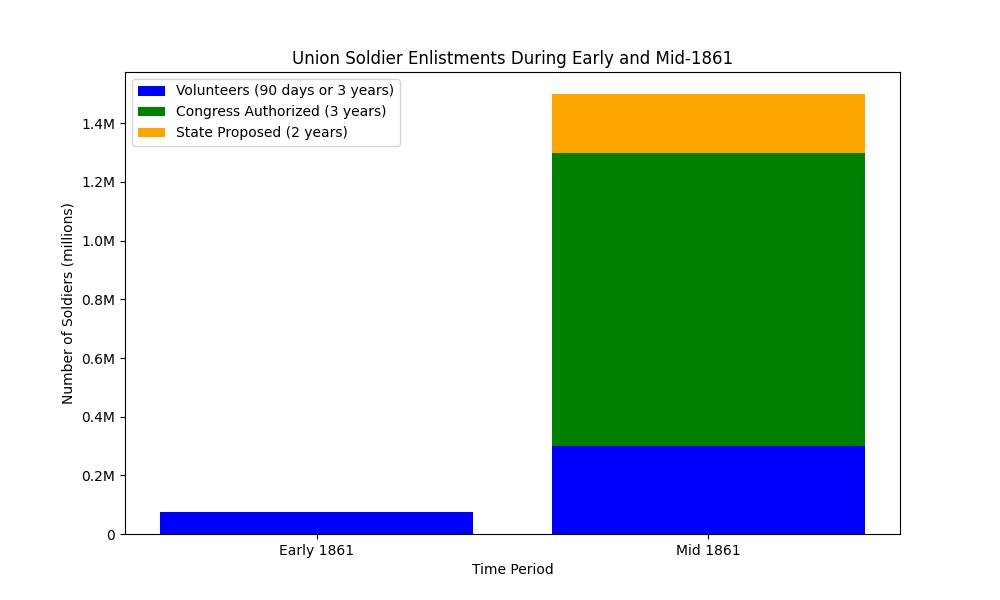

The American Civil War, one of the largest conflicts in American history, needed both volunteers and conscripts to keep the war effort going. In early 1861, President Abraham Lincoln initially called for 75,000 soldiers to serve for ninety days. However, it quickly became clear that this number would not be enough for a war that was escalating and showing no signs of ending soon. Consequently, Lincoln requested 300,000 men for three-year enlistments, and Congress authorized 1,000,000 enlistments for the same term. During this period, the War Department also accepted many two-year enlistments proposed by states that had advanced their own war efforts in favor of the Union.

In 1862, Congress passed the Militia Act, allowing the federal government to use state recruitment and take control of the militias raised. Despite these measures, by 1863, the Union forces still struggled to maintain their strength. To address this, Congress enacted the Enrollment Act of 1863, instituting a draft scheduled to begin in July of that year. This draft required all men between the ages of 20 and 45, including American citizens and non-citizens aspiring to become citizens, to enlist. However, those drafted could avoid service by either finding a substitute or paying $300 to the government. The Confederacy had a similar system, exempting individuals who owned plantations with more than twenty enslaved people from their draft.

In both the North and the South, exemptions to the draft sparked significant conflict. Many Northerners disapproved of wealthier Americans' ability to buy their way out of the war, while Southern farmers resented that rich plantation owners were exempt from fighting. Each congressional district had to meet a specific quota, and if this quota was not met, provost marshals were authorized to draft men to fulfill it. This process resulted in Democratic districts having more men drafted compared to Republican districts, where there were more pro-war citizens, causing major contention among the opposition. Another source of anger against the draft was the exemption of African-Americans, who, not being recognized as citizens, were initially not allowed to serve in the Army (though the United States Navy accepted them from the start of the war). This policy remained until 1863, further fueling resentment and opposition to the draft system.

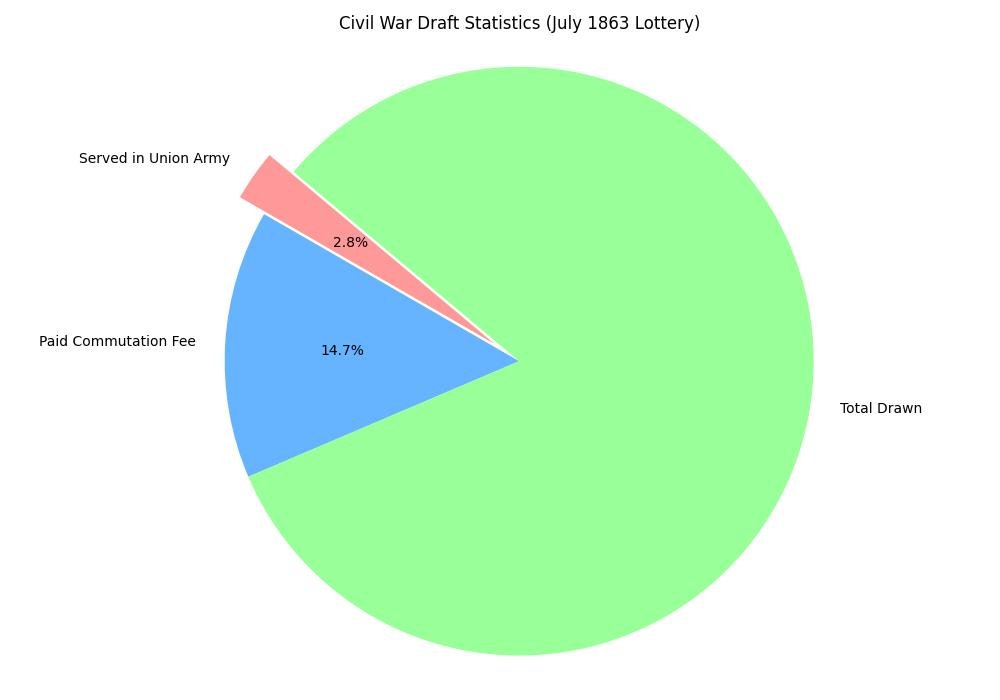

However, despite popular opinion among many who opposed or were unwilling to fight in the Civil War, the draft was not simply a mechanism for wealthy Yankee Protestants to force the poor into their war against slavery. Although the $300 commutation fee existed, private organizations and local governments often paid the fee for individuals, reducing the burden on lower-class Americans who did not wish to be drafted. Despite these measures, opposition to the draft remained strong. Of the 292,441 names pulled during the July 1863 lottery, only 9,881 ended up serving in the Union Army, constituting just 3.4% of those drawn. In contrast, 52,288 men paid the $300 commutation fee. Throughout all four drafts that were called, more than triple the number of men either paid the commutation fee or found a substitute, whose price often did not exceed $300 due to the commutation fee cap—a provision not present in the Confederacy.

On July 11, 1863, the draft lottery began in New York City without incident. However, on July 13, a mob formed in opposition to the draft, launching a violent campaign against Federal property, Republican newspaper offices, and African-Americans. The rioters lynched African-Americans, attacked their businesses, and destroyed the Colored Orphan Asylum, though many inside managed to escape. Governor Seymour, upon learning of the riots, went to New York City and delivered a speech calling for peace while criticizing the draft and pledging to request its suspension in the state. He later issued a proclamation urging those involved in the riots to return to their homes, warning that he would use all necessary power to restore order. The riots continued until Federal troops from Pennsylvania were deployed to quell the unrest. A month later, the draft resumed, but by then the New York City Council had allocated $2,000,000 for draft commutations to those who could prove that conscription would cause hardship to their families. Additionally, the City Council voted to provide $2,000,000 for those who had lost property during the riots, with $970,000 eventually spent. The riots resulted in 119 deaths, with most casualties occurring due to the mob's actions and the government's response.

The Federal response and the efforts of other organizations to limit the number of those drafted prevented similar riots in other cities. Unlike the Confederacy, the North did not experience widespread violent opposition to the draft that could hinder the war effort. Although the narrative that the rich were forcing the poor to fight existed on both sides, the North's commutation fee kept the price of substitutes around $300. Additionally, bounties for re-enlisting and new enlistees in the Union Army helped reduce the need for the draft, which ultimately brought only 46,347 men into service across four drafts. Many were exempted for various reasons, and local governments or private organizations often paid the commutation fee, making it accessible to most Americans.

Criticism of the draft in both the Union and the Confederacy often centered on the perception that it forced the poor or common person to fight a rich man’s war. This sentiment was expressed by many Peace Democrats and poor Southern farmers, who saw the conflict as either a crusade for the liberation of enslaved people in the South or as a means to protect the interests of large landowners. The Union draft law, which allowed for commutation, and the Confederate law, which exempted plantations with twenty or more enslaved people, exacerbated these tensions. Despite the societal friction it caused, the draft provided a small but vital source of manpower for the Union Army and created incentives to enlist or reenlist. The fear of being drafted prompted many to volunteer, raising more men for the Army than the draft itself, thereby bolstering the Union war effort. For those determined to avoid service, numerous avenues were available, whether through commutation fees, finding substitutes, or seeking exemptions, ensuring that those truly unwilling to serve had options to evade conscription.

Citations

Cooper, Douglas. STUMBLING towards TOTAL CIVIL WAR: THE SUCCESSFUL FAILURE of UNION CONSCRIPTION 1862-1865. apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA326566.pdf. Accessed 31 July 2024.“Doings of Gov. Seymour.; PROCLAMATION from the MAYOR.” The New York Times, 15 July 1863, www.nytimes.com/1863/07/15/archives/doings-of-gov-seymour-proclamation-from-the-mayor.html. Accessed 31 July 2024.

Fuller, A. James. “The Draft and the Draft Riots of 1863.” Bill of Rights Institute, billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/the-draft-and-the-draft-riots-of-1863.

Garber, Robert. “The New York City Civil War Draft Riot Claims Collection.” NYC Department of Records & Information Services, 22 Mar. 2024, www.archives.nyc/blog/2024/3/22/the-new-york-city-civil-war-draft-riot-claims-collection#:~:text=The%20City%20Council%20and%20Board. Accessed 31 July 2024.

Luebke, Peter. “African Americans in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War.” Public1.Nhhcaws.local, 10 May 2021, www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/civil-war-archive1/african-americans-in-the-u-s--navy-during-the-civil-war.html.

McGill, Sean, et al. “Enrollment Act: March 3, 1863 · New Paltz in the Civil War · Hudson River Valley Heritage Exhibits.” Omeka.hrvh.org, omeka.hrvh.org/exhibits/show/new-paltz-in-the-civil-war/laws/enrollment-act--march-3--1863. Accessed 31 July 2024.

Mcpherson, James M. The Illustrated Battle Cry of Freedom : The Civil War Era. 1988. New York, N.Y., Tess Press, 2008.

Stephens, H. L. (Henry Louis), and Printed Ephemera Collection (Library of Congress) DLC. “The Meeting of the Friends, City Hall Park.” www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661655/, 1863.

“Who Fought?” American Battlefield Trust, 12 June 2018, www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/who-fought.