The Battle of Plassey: Most Significant Battle in Modern History

One could argue that no battle has had a more profound impact on modern history than the Battle of Plassey. It is a tale of treachery, strategy, and timing. As the British historian Thomas Macaulay said, “No oath which superstition can devise, no hostage, however precious, inspires a hundredth part of the confidence which is produced by the ‘yea, yea’ and ‘nay, nay’ of a British envoy” (Macaulay, History of England). With the great victory, the British would become increasingly bolder and eventually control much of the eastern hemisphere’s trade and wealth. The Battle of Plassey stands as the most pivotal event in the history of European involvement in the eastern hemisphere due to its wide ranging impacts on economics and inequality.

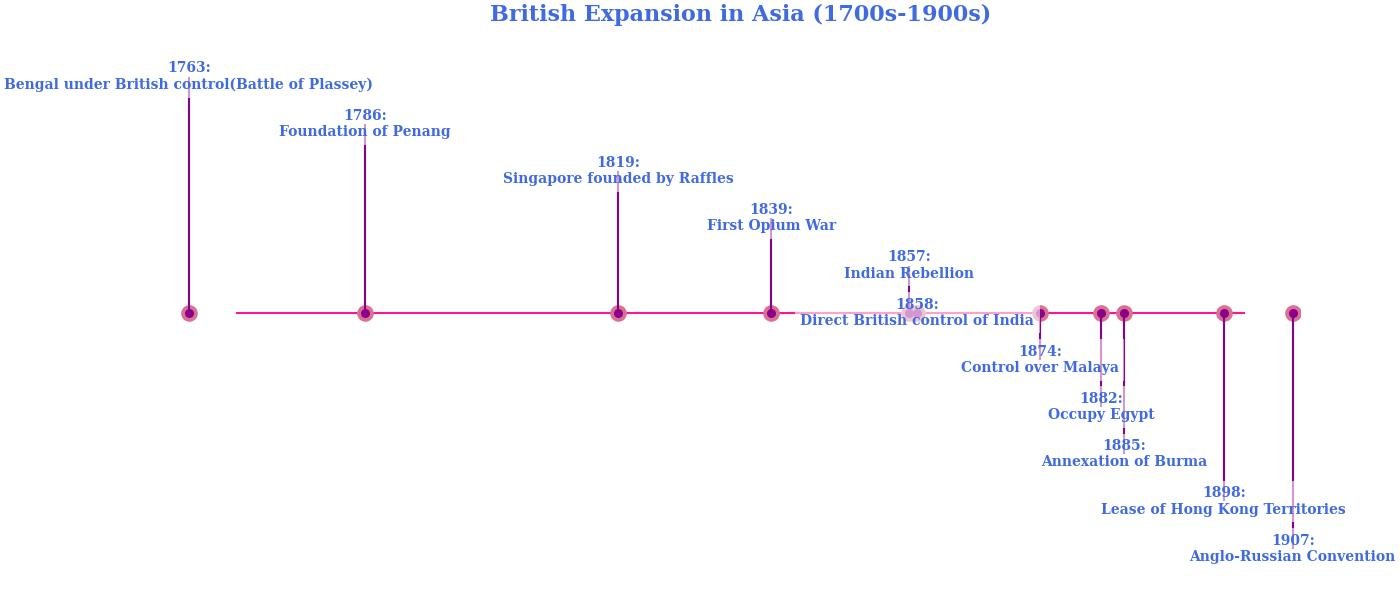

On the world stage, the British East India Company and French East India Company were dominant economic powers. From 1746, these rival companies engaged in the Carnatic Wars, vying for economic supremacy in India. These ongoing tensions set the stage for a decisive battle that would determine the future of trade and power in the region.

The combination of external and internal disputes led to the downfall of Siraj ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal. Siraj had strengthened his ties with the French, posing a significant threat to the British East India Company's dominance in the region. Within Siraj's own government, there were fears that he would seize their wealth for his own ends. An influential family, the Seths, and the British East India Company secretly conspired to make one of Siraj’s generals, Mir Jafar, the Nawab of Bengal if Siraj was defeated in battle. Both sides deemed a regime change necessary.

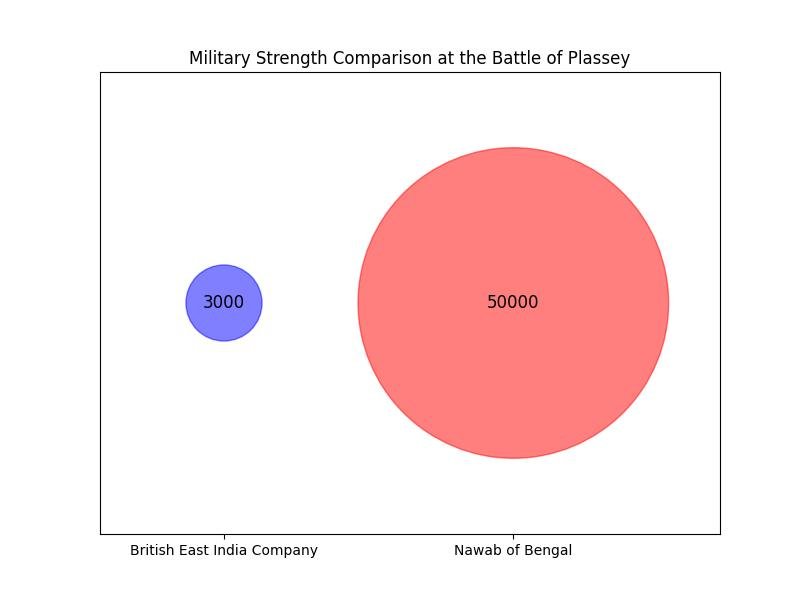

It was June 23 in the year 1757. Led by Robert Clive, the British East India Company fielded a force of 3,000 men, comprising 2,100 Indian infantry and about 800 Europeans. Clive's artillery was limited to ten field guns and two small howitzers. In contrast, the opposing army, commanded by the Nawab, boasted 50,000 men, including 16,000 cavalry. Their arsenal significantly outmatched Clive's, with a formidable array of 50 field guns.

The armies met near the small town of Plassey, along the Bhagirathi Hooghly River. From the outset, the Nawab’s army was disorganized, and their weapons were faulty. A heavy downpour worsened the condition of his troops, while the British artillerymen quickly capitalized with their cannons and ammunition. Despite this, the Nawab continued to push forward, unaware that his cavalry, led by Mir Jafar, refused to take part. Clive’s army routed the Nawab’s forces, inflicting over 500 casualties while sustaining only 72 of their own. Following the battle, Mir Jafar would kill Siraj ud-Daulah and was appointed the new Nawab of Bengal. However, he became a puppet ruler, and Bengal effectively became a colony of the British.

The rich and wealthy families of Bengal had initially welcomed the British victory, but it would become “an unsavory beginning and something of that bitter taste has clung to it ever since” (Nehru, The Discovery of India). The British had promised economic stability, but it became clear that they were only interested in exploiting resources for their own gain. The British enjoyed a slew of victories achieved with a mixture of military domination, bribes, and false promises. The Permanent Settlement of 1793, for example, fixed land revenue that landlords had to pay to the Company, which often led to excessive renting fees and widespread peasant indebtedness. Additionally, the introduction of cash crops for export, such as indigo and opium, disrupted traditional agricultural practices and led to food shortages and famines. These policies ensured that the wealth generated in India flowed to Britain, with the cost of exacerbating economic inequalities and impoverishing the Indian population.

The Company transitioned from being the primary British traders in the region to the rulers of India. With it came injustices and hardships for the local population, including oppressive taxation, the disruption of traditional economies, and the exploitation of India's vast resources. Injustices became increasingly prevalent, accompanied by a growing British attitude of superiority toward Indians. Where there had been a relative balance, the British began imposing their cultural norms, often criminalizing aspects of Indian culture. The introduction of English as the medium of instruction in schools, as mandated by Lord Macaulay's Minute on Education in 1835, devalued indigenous languages and knowledge systems. Social reforms like the ban on Sati (widow immolation) in 1829, while progressive, were often implemented with little regard for local customs and sentiments, leading to a perception of cultural imperialism. The Indian Penal Code of 1860 and other legal frameworks often had provisions that discriminated against Indians. Europeans accused of crimes against Indians were tried by jury panels that included other Europeans, leading to biased verdicts. The Ilbert Bill controversy of 1883, which proposed allowing Indian judges to preside over cases involving Europeans, highlighted the deep-seated racial prejudices within the colonial administration. The new rulers' disdain for Indian traditions and practices led to widespread social and cultural repression, fostering resentment and resistance among the Indian people. It is striking to realize that a battle fought near a small village marked the beginning of such profound suffering for the Indian populace.

On the world stage, the British had achieved a victory that cemented their dominance in the eastern hemisphere. The Nawab’s huge force included a significant number of French soldiers. With his defeat, the French were no longer a force in Bengal. The new influx of revenues and resources helped the British push their European colonial rivals, the French and the Dutch, out of the rest of India. Capital from the colonies was invested in building factories, railways, and ships, accelerating industrial growth and technological innovation. This industrialization gave Britain a significant advantage in global trade, allowing it to dominate international markets and establish a global economic order. Eventually, the British would rule over the subcontinent and fully control its wealth. For the next two centuries, the children of India would learn of the battle and the great “Clive of India”.

Furthermore, the British victory at Plassey provided a launching pad for their further expansion into other nations in Asia, most notably China. Buoyed by the consolidation of power in India and the lucrative trade opportunities it offered, the East India Company sought to capitalize on its newfound influence and wealth. Expanding their monopoly on English trade from India to China, the Company imported coveted goods like porcelain and tea to Great Britain and its colonies. However, this expansion also marked the beginning of tensions with China, particularly as British imports flooded Chinese markets and the opium trade escalated.

The widespread abolition of slavery in the 19th century and success in British expansion ushered in a new era of indentured servitude. Indentured workers, derogatively referred to as ‘coolies,’ were recruited from nations across the Pacific, including India and China, to fill the labor void left by emancipated slaves. These individuals signed contracts to work in British colonies such as Fiji, Mauritius, and the Caribbean, lured by promises of wages and opportunities for a better life. However, the reality they faced was far from the false picture painted by recruiters. Instead, they endured harsh working conditions, often toiling on plantations and in other industries for minimal wages and facing brutal treatment at the hands of overseers. These developments underscored the far-reaching consequences of the Battle of Plassey, not only within India but across the broader Asian continent.

The legacy of the Battle of Plassey shapes the socio-economic and political landscape of modern Asia. Wealth disparities are still evident in many former colonies, and the gaps in infrastructure and modernization are glaring. The injustices triggered by the events at Plassey have fueled discussions about the need to rethink history.

Ciations

Battle of Plassey | National Army Museum. (2024). Nam.ac.uk. https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/battle-plasseyBattle of Plassey | Summary | Britannica. (2024). In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Plassey

Battle of Plassey | MANAS. (2016). MANAS. https://southasia.ucla.edu/history-politics/british-india/battle-of-plassey/

Chatterjee, A. K. (2018, June 23). The Battle of Plassey was fought on June 23, exactly 261 years ago. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/society/history-and-culture/armenians-clive-and-the-battle-of-plassey/article24230759.ece

The British Impact on India, 1700–1900 - Association for Asian Studies. (2023, June 15). Association for Asian Studies. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-british-impact-on-india-1700-1900/

The British East India Company. (2023, December 6). American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/british-east-india-company

The History of England from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688, Foreword by William B. Todd, 6 vols. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1983). Vol. 1.

Nehru, Jawaharlal, 1889-1964. (19591960). The discovery of India. Garden City, N.Y. :Anchor Books.

Macaulay’s Minute on Indian Education. (2024). Ucsb.edu. http://oldsite.english.ucsb.edu/faculty/rraley/research/english/macaulay.html

Indian Penal Code, 1860. (2022). A Lawyers Reference. https://devgan.in/ipc/

Ilbert Bill | Indian Reform, Education & Legislation | Britannica. (2024). In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Ilbert-Bill#:~:text=Ilbert%20Bill%2C%20in%20the%20history,25%2C%201884

McLane, J. R. (1981). The Permanent Settlement in Bengal: A Study of Its Operation, 1790–1819. By Sirajul Islam. Dacca: Bangla Academy, 1979. xv, 288 pp. Glossary, Appendixes, Select Bibliography, Index. Tk. 25. the Journal of Asian Studies/the Journal of Asian Studies, 40(4), 827–828. https://doi.org/10.2307/2055727

Indentured labour from South Asia (1834-1917) | Striking Women. (2024). Striking-Women.org. https://www.striking-women.org/module/map-major-south-asian-migration-flows/indentured-labour-south-asia-1834-1917