The Kansas and Nebraska Act

The Kansas-Nebraska Act stands out as a critical moment in the lead-up to the American Civil War, stirring up significant tensions across the nation. Coming on the heels of the Mexican-American War, this legislative move further fueled the already simmering discord between the North and South. While President James Polk's focus on negotiating with Britain over Oregon diverted attention away from the complete annexation desired by many expansionists, the Kansas-Nebraska Act sparked a rush of activity. Both Northerners and Southerners flooded into the newly created Kansas Territory, each vying to sway the Territory’s stance on slavery. This led to a series of heated and sometimes violent debates and the drafting of several controversial constitutions, highlighting the deep divide plaguing the nation and causing the rise of the Republican Party. As well as further weakening the Whig Party, setting the stage for the bloody conflict that would soon follow.

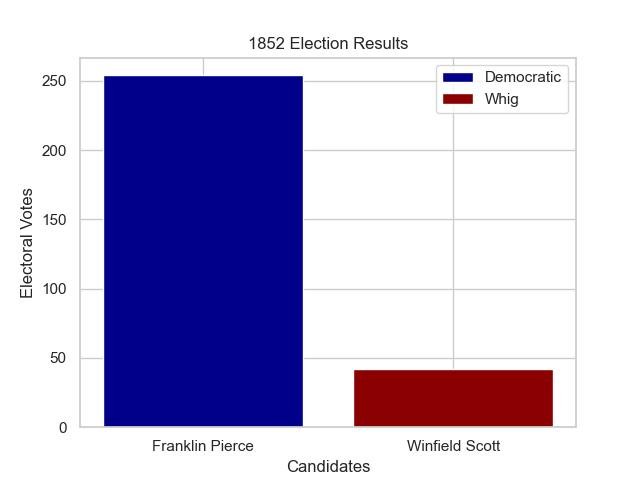

The Whigs had formed in opposition to the Democrats during the presidency of Andrew Jackson and had opposed free trade and the destruction of the Second Bank of the United States. However, they failed in their legislative goals during their control of Washington in 1841, due to President John Tyler’s veto. Having only won 42 electoral votes in the previous presidential election due to an inability to maintain party unity, the Whigs were already facing challenges. In the midst of this situation, the battle for Kansas's future embodied the growing rift between the North and South.

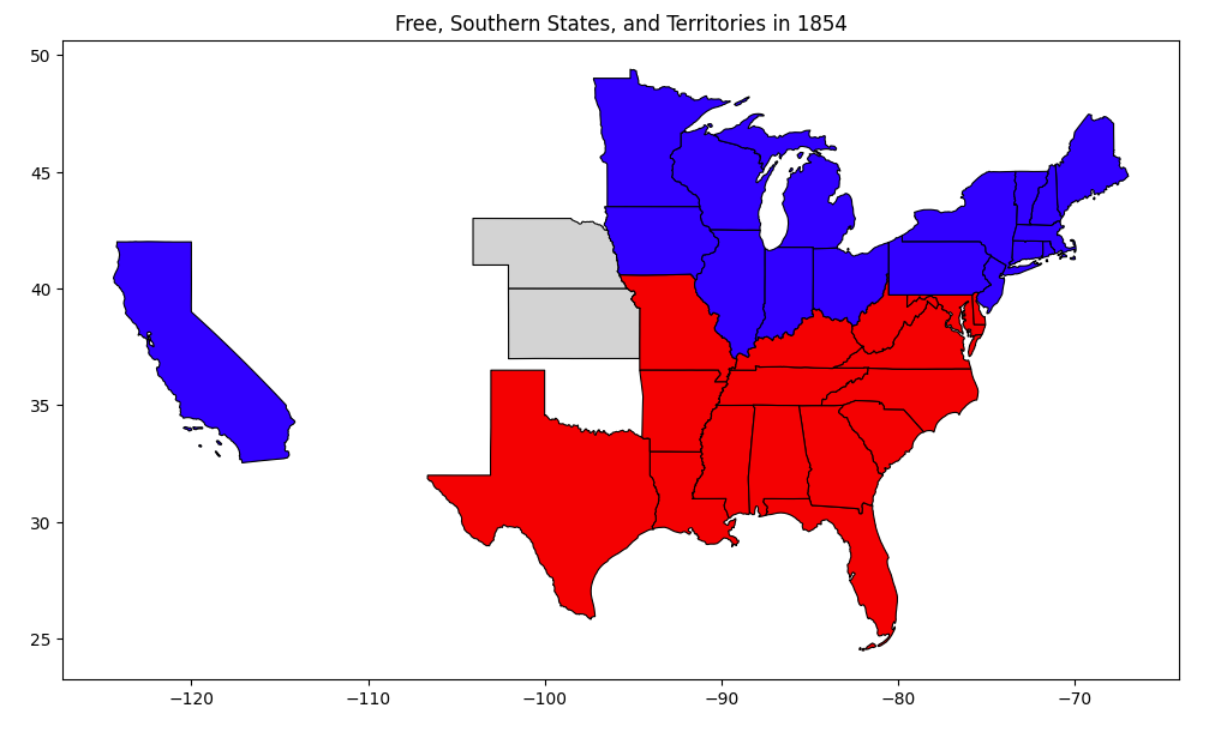

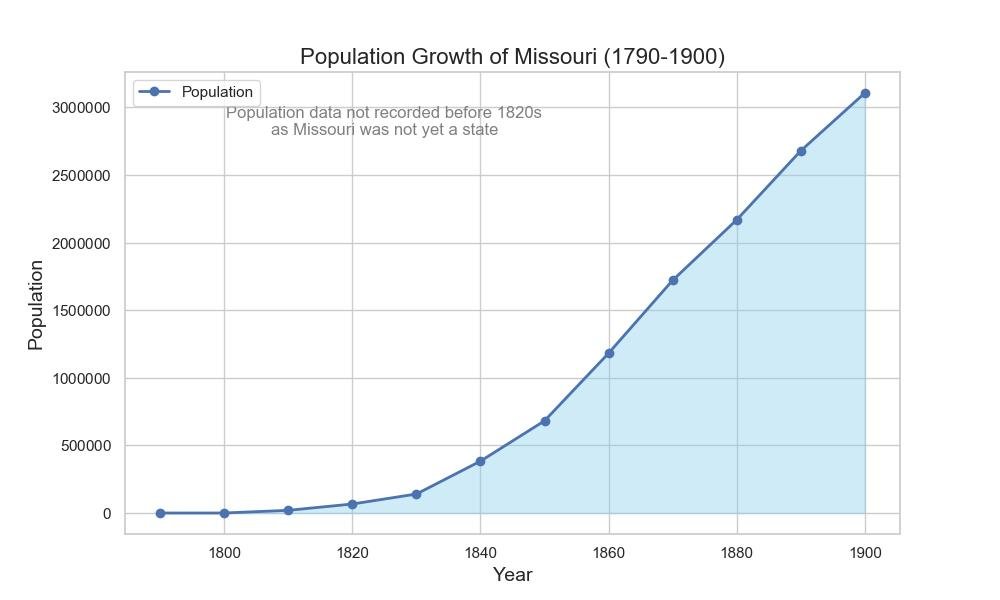

The legislation was initially created as an attempt to further organize the Louisiana Territory and build a transcontinental railroad from Illinois to California. Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas believed that Kansas should be another exception to the Missouri Compromise because most of the land gained from the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo wasn’t suitable for cash crops. Pro-Slavery Southerners opposed maintaining the Missouri Compromise for Kansas and Nebraska because that would mean that Missouri would border free states on three sides and that there would be more free states with representation in the Senate, which has representation based on the number of states. This was the reason for the Missouri Compromise. Therefore, they promoted the idea of popular sovereignty, the concept that each state should decide by popular will if it is to be a free state or a slave state, rather than the 36°30' line determining that.

Senator David Atchison, a staunch advocate for slavery in the United States Senate, vehemently pushed for the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. His aim was to open up the possibility of slavery extending into the Nebraska Territory, thus preventing Missouri from being nearly encircled by free states. Faced with this demand, Senator Stephen Douglas found himself at a crossroads: either maintain the bill's original terms and risk its failure in Congress, or compromise with Southern interests, risking outrage from the North. The prospect of a new slave state emerging above the Mason-Dixon line loomed large, particularly in the southern portion of the still-unorganized Kansas Territory, where slavery was permitted. Meanwhile, Nebraska, located to the north, was also a key area for Southern Democrats, similar to the agricultural landscape of neighboring Missouri. However, this plan drew fierce opposition from abolitionists, who saw it as a violation of the Missouri Compromise. This landmark agreement had sought to maintain a delicate balance between free and slave states, designating Missouri as the last slave state north of the designated line at 33’30’, a line intended to divide the nation evenly.

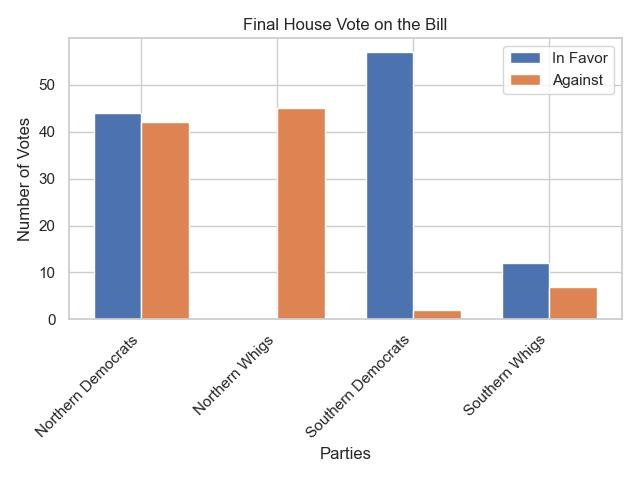

Despite widespread Northern outrage, the bill secured passage in the Senate by a vote of 41-17 and in the House by a narrow margin of 115-104. Surprisingly, a significant number of Northern Democrats supported the measure. However, their support came at a political cost, as the majority of them failed to win re-election. Only seven of those who had voted in favor of the bill managed to retain their seats, underscoring the deep divisions and political consequences sparked by the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

The fallout from the Kansas-Nebraska Act ignited a firestorm of anger in the North, as it violated the fragile balance established by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. While the Compromise of 1850 had granted territories acquired from the Mexican-American War the right to determine their own stance on slavery, Senator Stephen Douglas sought to extend this principle to the vast Louisiana Territory. This bold move, however, flew in the face of the longstanding Missouri Compromise, which had maintained peace for over three decades by laying out free and slave territories. The Act's passage kicked off a period of internal conflict within the Kansas Territory, marked by violent clashes between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions. This unrest foreshadowed the eruption of the American Civil War in 1861.

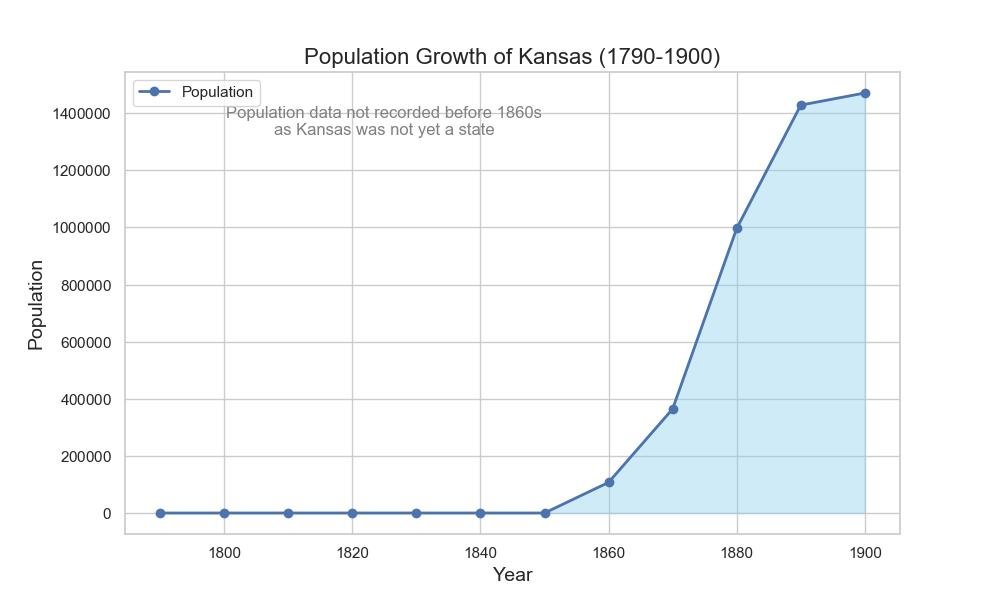

In the aftermath of the bill’s passing, there was a huge influx of migration into the Territory of Kansas. This was because of the concept of ‘popular sovereignty’, which said that the populace of a state should decide on the legal status of slavery within its borders. Because of the monumentous implications of the Kansas-Nebraska Act this led to both northerners and southerners entering the territory in order to make the state free or slave respectively. This became known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’, due to the violence caused by those trying to form a free or slave constitution for Kansas. When pro-slavery agitators attacking Lawrence, Kansas. Bleeding Kansas’ violence was exacerbated. With pro-slavery advocates trying to make the Lecompton Constitution the constitution for the State of Kansas, which included pro-slavery provisions and was supported by President James Buchanan. While there was a free government in Topeka, which would encompass a growing number of residents in the state. Due to all this Senator Charles made a speech by the name of “The Crime Against Kansas”, which would end up with him beaten by Senator Brooks of South Carolina afterwards. The Lecompton Constitution failed to pass during this time and the state would become a free state upon the beginning of the American Civil War, which would settle the issue of slavery in Kansas.

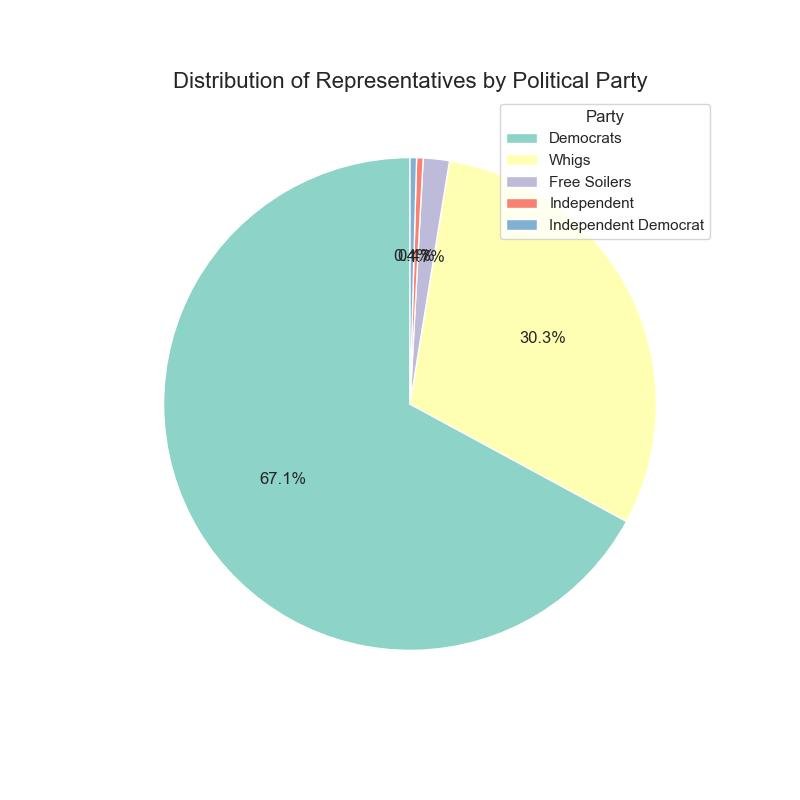

Politically, the Whig Party faced significant challenges as many Southern voters turned away from them, gravitating instead towards the Democratic Party due to the divisive issue of slavery. Meanwhile, among their Northern supporters, there was a lack of consensus on party affiliation, particularly evident in the 1854 Congressional elections, in which the Democrats lost the House majority and many anti-Nebraska parties formed and won seats in Congress. Therefore, in 1855, 133 votes for the Speaker of the House took place before a viable anti-Democratic coalition could be found. These elections saw the Democratic Party suffer losses, losing its majority in the House while maintaining the Senate. Despite this setback, the Democrats remained the largest party in Congress due to their dominance in the southern states, a trend which would continue for more than a century. The political landscape of the time reflected the growing regional polarization over the issue of slavery, which continued to reshape party dynamics and electoral outcomes in the years leading up to the Civil War.